KWM INSIGHT SERIES – CRITICAL MINERALS

At the 28th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28):

‘… 22 countries, including all five Sapporo 5 members, pledged to triple nuclear energy capacity by 2050 – marking a monumental shift for the world’s second largest source of clean power.’[1]

In 2023, the Sapporo 5 (a strategic partnership between the United States, Canada, France, Japan, and the United Kingdom) agreed to collaborate to develop a secure and resilient global nuclear supply chain.

Further, COP28 formally recognised and called on the parties to the Paris Agreement to contribute to the global efforts in (amongst other things) accelerating zero and low-emission technologies including nuclear in the “First Global Stocktake of progress towards meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement”.[2] The Nuclear Energy Agency Director-General welcomed this, saying “The OECD Nuclear Energy Agency welcomes the outcome of the COP28 global stocktake, which for the first time acknowledges the crucial role that nuclear energy could play in helping countries to lower their carbon emissions. Global emissions must reach net zero by 2050.”[3]

As Australia has the largest uranium reserves in the world, accounting for approximately one-third of global resources, and is the fourth largest producer (behind Kazakhstan, Canada, and Namibia), it is clear that Australia will have a significant role to play in the global supply chain for uranium to support those global efforts.

As highlighted in our last insight in this Critical Minerals series regarding copper, the Australian Government classifies various minerals as “Critical Minerals”, while other minerals might be classified as a “Strategic Material” (e.g., where required for the energy transition, AI, and other future technologies). As a result of Australia’s high uranium reserves and low domestic demand, uranium is not classified as a Critical Mineral or a Strategic Material but nevertheless it will play an essential role in the energy transition and future technologies globally.

In this insight, we consider the current global uranium supply chain for use in nuclear power generation, and Australia’s role in this global supply chain.

Uranium and its uses including fuelling the energy transition

The most common use for uranium is as the vital component for the production of nuclear fuel, in addition to various medical, industrial and defence applications including in medical radiation therapy.

Nuclear power currently accounts for about 10% of all electricity generation globally, with operational nuclear power plants in 31 countries worldwide.[4] This figure is expected to continue to rise, with many countries recently taking steps to both extend operations at existing nuclear power plants and build new ones:

- In February 2022, France announced plans to build a further 6 new nuclear reactors to bolster the power generated from the existing 56 operative reactors already in service,[5] and earlier this year, the ‘energy sovereignty bill’ referred to at least six but possibly a further 14 new reactors to meet France’s climate change goal.[6]

- The Biden-Harris administration has undertaken a number of actions which represent the ‘largest sustained push to accelerate civil nuclear deployment in the United States in nearly five decades’.[7] Noting that “[f]or decades, nuclear power has been the largest source of clean energy in the United States”, those actions include steps to keep existing nuclear plants operational, support the demonstration and deployment of advanced reactor technologies, and make permitting processes more efficient and effective.

- Japan established a law in 2023 under the Green Transformation initiative that allows power companies to operate nuclear assets for longer, in some cases over 60 years, by excluding periods during which they were suspended for safety reasons.[8]

- China continues to lead in nuclear capacity additions, with two large reactors completed in 2022, four more starting construction and plans to further accelerate deployment.[9]

- The UK currently has nine operative reactors, with two new reactors under construction and government plans calling for up to 24GW of new nuclear capacity by 2050.[10] In May 2024, the UK government announced that it will be the first European nation to produce advanced nuclear fuel – a market currently dominated by Russia.[11]

The global uranium supply chain

Currently, about two-thirds of the world’s production of uranium from mines is from Kazakhstan, Canada, and Australia.[12] Mined uranium ore (containing uranium oxide / U3O8) must undergo a series of processes, including enrichment and fabrication, in order to produce a useable fuel for use in electricity generation. When it comes to processing, Russia is the largest uranium enrichment supplier on the global market, providing approximately 35% of global enrichment.[13] Russia is also the only commercial supplier of high-assay low-enriched uranium (HALEU) necessary for certain advanced reactor designs.[14]

In the current geopolitical context, several governments have recently announced moves to reduce dependence on Russia. For example, according to the International Energy Agency:

- In January 2023, the US Department of Energy announced awards to the conversion industry to develop its strategic uranium reserve.[15]

- In April 2023, Canada, France, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States announced an agreement to support the stable supply of nuclear fuel and “undermine Russia’s grip” on nuclear fuel supply chains.[16]

- Recently, both the United Kingdom and the United States have announced moves to encourage the development of HALEU enrichment capacity.[17]

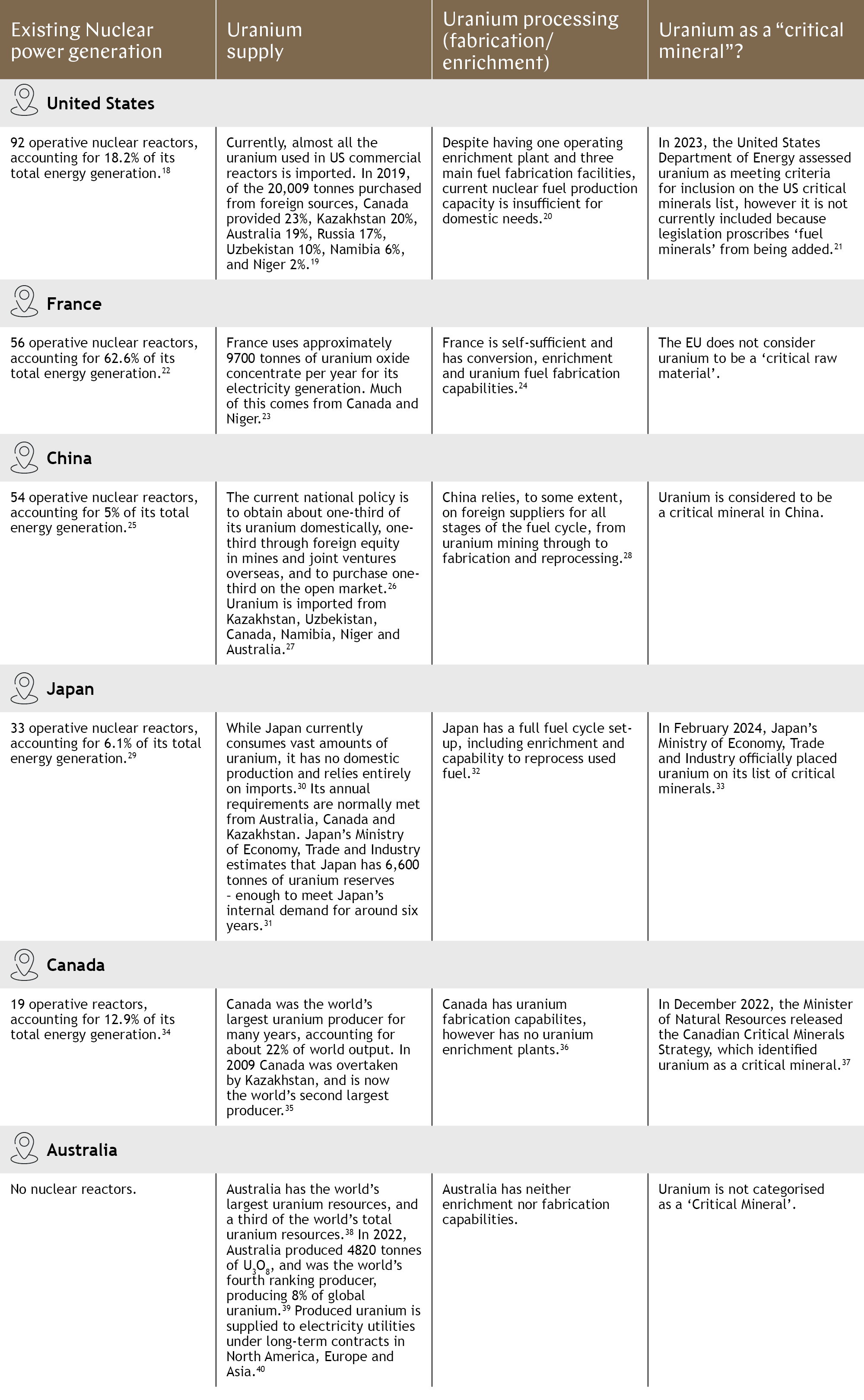

Nuclear power generation for Net Zero & uranium supply

The following table provides a snapshot of the current nuclear power generation and uranium mining and supply landscape in key jurisdictions, with countries listed in order of the ‘most-to-least’ number of operative nuclear reactors.

Click to expand image

Uranium classification and safeguards in Australia

Despite being considered a critical mineral in various jurisdictions - including Canada, Japan, and China - uranium is not currently categorised as a Critical Mineral by Australia.

As noted in our previous insight, a core factor for a mineral to be considered “critical” in most jurisdictions is supply chain risk, and the Australian categorisation of uranium as non-critical reflects that the relevant Critical Minerals / Strategic Materials tests are applied from a domestic perspective only. Critical Minerals are considered by the Australian Federal Government as metallic or non-metallic materials that are essential for modern technologies, economies, or national security, and have supply chains that are vulnerable to disruption.[41] By this definition, uranium’s exclusion from Australia’s Critical Minerals List (and Strategic Materials List) makes sense, as Australia produces a significant quantity of uranium which, with no domestic nuclear power plants, is effectively all subject to export.

Australia has significant legislative domestic safeguards and security standards for nuclear material (including uranium, plutonium and thorium) production and handling, and associated technology - these are framed in legislative requirements.

Uranium may only be exported for peaceful, non-explosive purposes under Australia's network of bilateral nuclear cooperation agreements, which provide for:

- safeguards (either International Atomic Energy Agency - or fallback – safeguards) and physical security requirements; and

- prior Australian Government consent for any transfer of relevant material to a third party, for any enrichment of uranium product beyond 20 per cent 235U, and/or for any reprocessing of that relevant material.[42]

Australia’s role in the global supply chain and its opportunity

As noted above, Australia has the largest uranium reserves in the world and is the fourth largest producer of uranium. South Australia, in particular, hosts approximately 80% of Australia’s economic demonstrated resources of uranium, and approximately 23% of the world’s uranium resources.[43]

Currently, the mining of uranium is only permitted within the Northern Territory, South Australia and Tasmania. Exploration for uranium is permitted in Queensland and New South Wales, however Victoria prohibits both exploration for, and mining of, uranium. Whist the exploration for, and mining of, uranium in Western Australia is permitted under the WA Mining Act, a state policy ban on mining approvals for uranium was reinstated in 2017 with a ‘no uranium’ condition on all future mining leases.[44] Until 8 January 2021, the operational uranium mines in Australia were Ranger in the Northern Territory, and Olympic Dam, Beverley/Four Mile and Honeymoon in South Australia. However, mining and processing activities were ceased at the Ranger mine in 2021 (with operations at Ranger now focussed on rehabilitation completion by 2026). Mining and processing activities were initially ceased at the Honeymoon mine in 2013; however, the project has since reopened and is expected to produce its first drum of uranium oxide during 2024.[45]

No enrichment or fuel fabrication is undertaken in Australia, and Australia exports all the uranium oxide concentrate that it produces. Australia’s uranium is exported strictly for electrical power generation only, in accordance with the Federal regulations which safeguard its use.[46]

Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Finland, France, Hungary, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden, and Ukraine all get 30% or more of their electricity from nuclear reactors.[47] As noted at the outset above, COP28 called for accelerating the deployment of low-emission technologies including nuclear energy to help achieve deep and rapid decarbonization, and 22 countries at COP28 (including the United States, Canada, France, Japan, and the UK) all pledged to triple nuclear energy capacity by 2050.[48]

Significantly more uranium would be required to meet the anticipated rising global uptake of nuclear power generation. Depending on the energy mix of zero-carbon and low-carbon technologies and their prioritisation through to 2050, there could be a huge export market opportunity for Australia to continue to grow into over the future years, particularly to assist the COP28 jurisdictions move towards their goal of tripling of nuclear capacity by 2050.