Nickel and the global energy transition

Given the growth of the electric vehicle (EV) industry and the corresponding demands of battery manufacturing, nickel is increasingly seen as a strategic metal anticipated to play a crucial role in the future energy transition.

- Indonesia’s nickel industry dates back to 1901 and today it has the highest reserves globally.

- Recent regulatory changes have modernised the mining industry including streamlined licensing, but more is needed to address ESG issues.

- The persisting total export ban on the raw nickel ore means that there will be a need for greater investment and development of in-country processing and refining facilities for locally mined nickel.

- Most foreign investment to date is in the upstream mining supply chain, but the government intends to promote the development of downstream processing and manufacturing capabilities.

- Indonesia is increasingly playing a crucial role in China’s nickel supply chain, by way of billions of dollars’ worth of Chinese investment in refining mega-projects.

- Integrated infrastructure is another key arm to its downstream hopes and nickel-powered EV ambitions – such as the planned US$1.1 billion construction of the country’s first EV battery plant, backed by the government and a LG and Hyundai-led consortium.

- Almost US$10 billion in total will go to building battery production onshore to increase Indonesia’s allure to big-name EV companies.

- To secure benefits under the Inflation Reduction Act (the “IRA”) and maximise access to the US market, Indonesia is pursuing a limited US-Indonesia Free Trade Agreement, which if materialised will bring with it greater access to the EV car market in the US.

While still primarily used as an important alloying addition to produce stainless steel, nickel has become a key component in lithium-ion EV batteries. Other ‘green’ applications for nickel include energy storage, hydrogen, wind and concentrating solar power. Nickel’s production and supply will have an immense influence on the clean energy transition and the future energy industry. Nickel, together with lithium and certain rare earths, is high in importance to energy technologies and high in supply risk in the medium-term (2025-2035). This is according to the 2023 Critical Materials Assessment released by the U.S. Department of Energy, which assesses materials for their criticality to global clean energy technology supply chains[1].

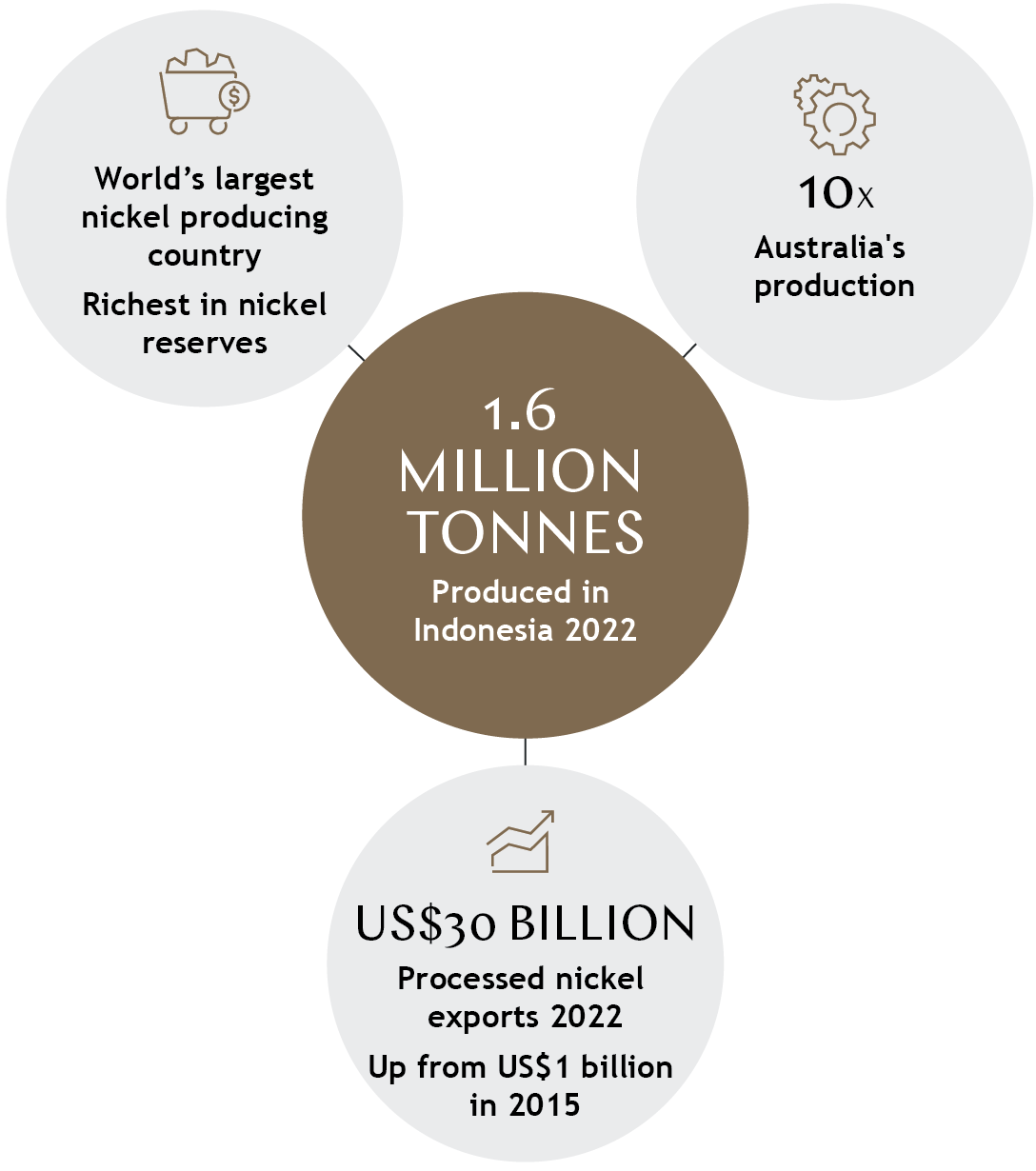

Tied with Australia, Indonesia has the highest nickel reserves in the world, coming in at 21 million tonnes (or a fifth of global reserves). In 2022 alone, Indonesia produced 1.6 million tonnes of nickel being 10 times more than Australia’s production[2], making Indonesia the world’s richest in nickel reserves and largest nickel producing country. Correspondingly, Indonesia’s exports of processed nickel reached an estimated US$30 billion in 2022 alone, an exponential increase from just US$1 billion in 2015[3].

The Indonesian nickel industry already plays an essential role in the global battery and EV industry, and it is likely to continue in such a role. Against this background, in this insight we look at the nickel industry in Indonesia, its recent developments and certain key issues being faced by the industry as it adapts to address the challenges of a rapidly changing economic, industrial and regulatory environment.

Indonesia and its nickel industry

Since the discovery of nickel ore in 1901 at the Verbeek Mountains in Sulawesi, Indonesia’s nickel industry has grown on an upward trajectory, with the majority of mines being located in the eastern provinces, primarily the Maluku and Sulawesi islands.

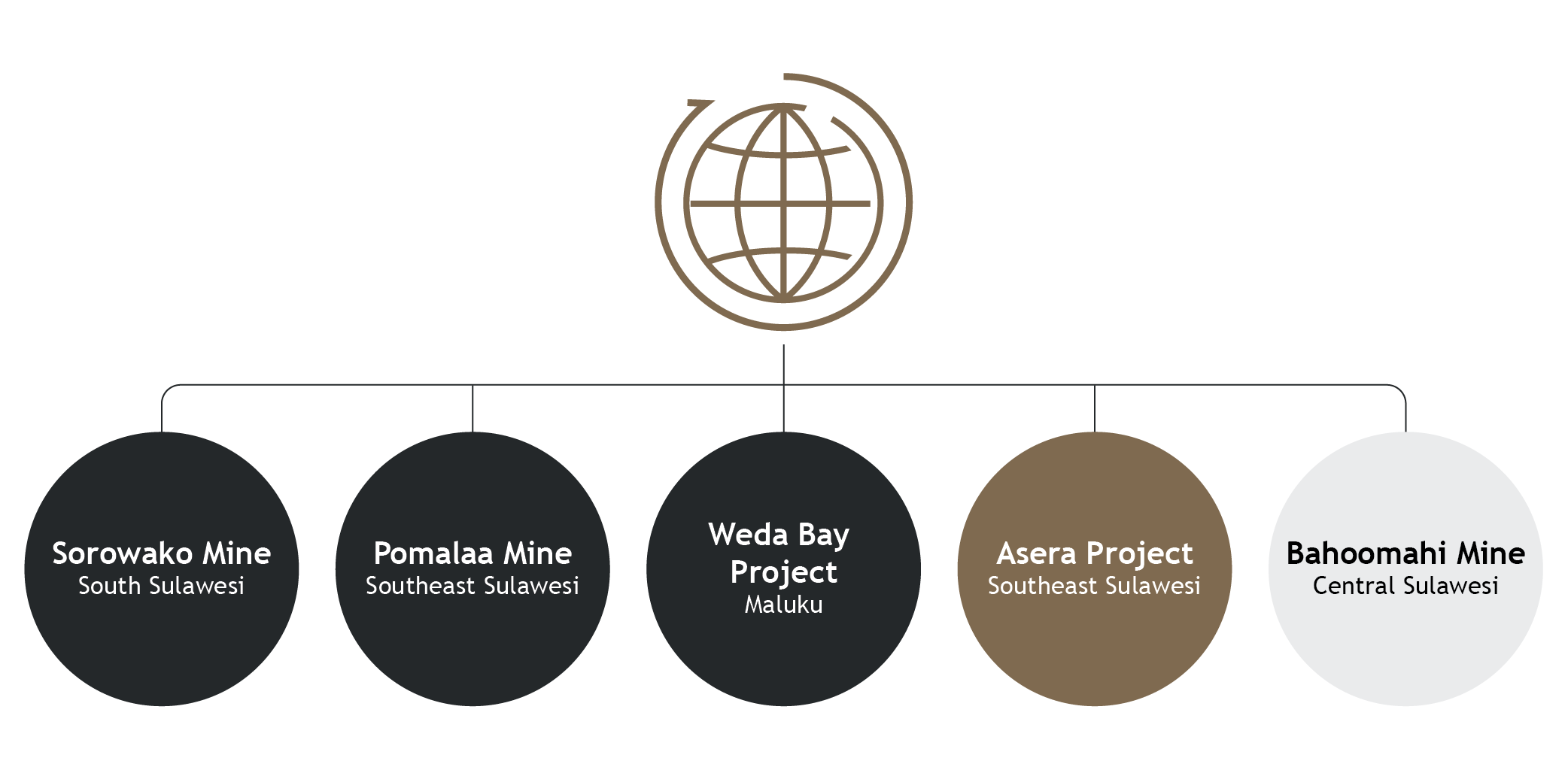

As of 2023, foreign investment into Indonesia’s metal industry has amounted to US$53.3 billion with most of this sizeable sum flowing into the nickel sector[4], led by Chinese companies who have been investing heavily into the local nickel industry (bringing the total to US$14.2 billion of Chinese investment over the past 10 years[5]). Notably, Tsingshan Group and Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt Co have a medley of interests in three of the largest mines in Indonesia, being the Sorowako Mine, the Pomalaa Mine and the Weda Bay Project (in Maluku). Together with the Asera Project (in Southeast Sulawesi) and the Bahoomahi Mine (in Central Sulawesi), these five mines are mostly owned and operated by foreign companies or in joint ventures with an Indonesian state-owned entity subjected to Indonesia’s foreign divestment rule. So far, most of the foreign investment have been in the development and operation of nickel mines, but as discussed below, the government’s intention is to promote the development of downstream processing and manufacturing capabilities.

Foreign investment in Indonesia’s nickel industry is led by China…

The most important Indonesian nickel ores are lateritic as opposed to sulphide deposits (being another common form of nickel minerals). Unlike sulphide deposits, lateritic nickel deposits are found at the surface and are generally mined from open pits by strip mining. After mining, the nickel contents in the nickel ores are then processed into nickel products which are classified into two classes (depending on the nickel purity levels): only Class 1 nickel is suitable for battery manufacture (as well as other speciality uses such as producing super alloys) while Class 2 nickel is more often used to produce stainless steel. Globally, most Class 1 nickel is produced from nickel sulphide ore but given that lateritic nickel is relatively more commonly found, there has been increasing interest in the usage of high-pressure acid leaching (HPAL) to process and produce Class 1 nickel from lateritic nickel ore. In the acid-leaching process, instead of melting the nickel ore[6], the nickel ore is placed in a pressure cooker-like machine (under conditions of intense heat and pressure) and mixed with sulphuric acid, which strips the nickel out from its raw ore to be converted into a higher-grade material suitable for EV batteries.

The reformation of domestic policies by the Indonesian government

To understand how, in particular, the domestic mining industry has evolved (and is continuing to evolve) in light of the country’s developmental and industrial objectives, we must examine the regulatory changes affecting Indonesia’s nickel mining policies.

A. Total export ban of raw nickel ore

(I) Implementation of the export ban

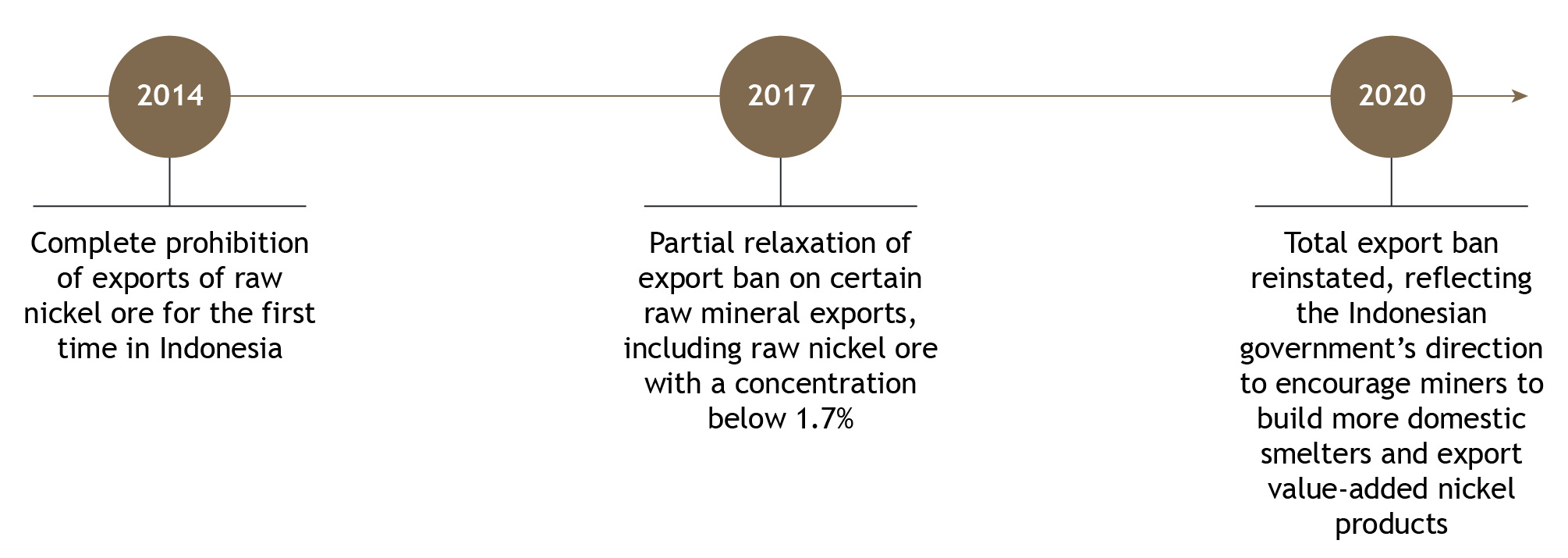

For a number of years, the Indonesian government has sought to restrict or ban the export of raw nickel ore, with the view to promote the development of higher value industrial activities in the sphere of nickel processing and refining. However, the path to securing this objective has not been without its challenges. Tracing back, exports of raw nickel ore were first completely prohibited in Indonesia in 2014[7]. In 2017, Indonesia partially relaxed the export ban by temporarily allowing exports of certain minerals, including raw nickel ore with a concentration below 1.7% so as to prop up its economy[8]. It was intended that a full export prohibition be reinstated on 11 January 2022. However, in August 2019 and two years ahead of schedule, the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR) announced the total export ban to restart in January 2020, two years ahead of schedule[9]. This ban reflected the Indonesian government’s direction to encourage miners to build more domestic smelters and export value-added nickel products.

(II) Response to the export ban

In response to the MEMR’s announcement regarding the total ban (again) on the export of raw nickel ore, the European Commission requested consultations with Indonesia at the World Trade Organization (WTO) in November 2019. As this did not lead to a resolution, the European Commission requested the establishment of a WTO Panel in January 2021, accusing Indonesia of unduly and illegally restricting EU access to raw materials needed for stainless steel production and of distorting world market prices of ores[10]. In November 2022, the WTO ruled against Indonesia’s nickel export limitations reasoning, inter alia, that each WTO member country is prohibited from imposing restrictions other than duties, taxes or other charges[11]. Despite the WTO decision (which is on appeal[12]) and the European Commission’s recent public consultations to decide on further punitive measures against the export ban[13], the Indonesian government has given no indication that it will back away from the ban.

To implement the export ban, the Indonesian government has also been cracking down on allegedly illegal shipments of nickel ore. A recent example is the joint agency investigation launched by the MEMR together with the Corruption Eradication Commission probing allegedly illegal shipments from early 2020, which in turn is estimated to have caused Indonesia millions of losses in royalties and export taxes.

Chinese investment in nickel processing in Indonesia has also noticeably increased, with various investments (in the billions) by Chinese companies such as Tsingshan Group and Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt Co in nickel smelting and refining projects in Sulawesi[14] and North Maluku[15] respectively. This can be perceived as a win for Indonesia’s government – by playing a crucial role in China’s nickel supply chain, such investment has served to move Indonesia closer to its objective behind its total export ban of attracting foreign investment downstream to create jobs and become an advanced manufacturing economy.

B. 2020 Mining Law

Shortly after the introduction of the export ban, on 10 June 2020, Indonesian President Joko Widodo signed a bill amending Law No. 4 of 2009 on Minerals and Coal Mining (2009 Mining Law), later ratified into Law No. 3 of 2020 (2020 Mining Law), which covers broadly the coal and mineral mining industry in Indonesia, including nickel. Overall, the 2020 Mining Law brought about a number of significant changes and streamlining effects to the regulatory requirements in the mining sector. Some are highlighted and further discussed below.

(I) Centralised licensing process

The 2020 Mining Law implemented a centralised licensing process whereby the MEMR now has exclusive authority to issue mining business licenses (otherwise known as “IUPs”, “IPRs” or “IUPKs” in Indonesia, amongst other licenses[16]). Previously, a mining company had to deal with local bureaucracies when applying for a license to carry out inter-province mining operations. By concentrating the licensing process at the central level of government (through the MEMR), processes instituted at a provincial level are cut out to facilitate an ease of doing business especially for foreign companies[17].

(II) Singular IUP for a mining company’s exploration and production operation activities

Prior to the 2020 Mining Law coming into effect, the two most common forms of IUPs were:

(i) Exploration IUPs which granted its holder the rights to conduct surveyance, exploration and feasibility studies on the mining site, and

(ii) Production Operation IUPs which granted its holder the rights to mine, process and refine the mineral in question.

Back then, a Production Operation IUP must be obtained by a mining company so that it could proceed to the production operation stage after completion of its exploration activities under the Exploration IUP[18]. This process was revamped and simplified under the new 2020 Mining Law.

A singular IUP termed “Mining Business License” now covers both activities, replacing the previous two IUPs. Exploration IUP holders are no longer required to apply to upgrade their existing IUP to proceed to conduct mining, processing and/or refining activities after exploration (see footnote 18) but this ‘automatic’ upgrade is subject to them fulfilling the requirements as stated in their Exploration IUPs.

(III) Government-guaranteed extensions of IUPs

In a bid to incentivize the development of downstream nickel mining industry, the 2020 Mining Law guaranteed the extension of miners’ licences to grant them business certainty to invest significantly in their own downstream facilities and add value to commodities before export. Mining companies with processing and/or refining facilities integrated into their mining operations (where they do not just focus on mining the nickel but rather cover both upstream and downstream nickel production) are entitled to a production operation term of 30 years with another guaranteed 10 years for each license extension request (such extensions could be granted without limitation) compared to non-integrated mining companies (i.e. operating only processing and/or refining facilities, or only mining facilities[19]) capped at a 20-year operation term with two guaranteed extensions of 10 years each.

(IV) Streamlined licensing for processing and refining activities

Before the 2020 Mining Law was introduced, non-integrated mining companies could be considered as coming under the authority of the MEMR and/or the Ministry of Industry (MOI) depending on their scope of business activities. The respective ministries issued different licenses and so to err on the side of regulatory compliance, non-integrated mining companies applied for both a Special Production Operation IUP from the MEMR as well as an Industrial Business License (IUI) from the MOI. The 2020 Mining Law has abolished Special Production Operation IUPs to avoid further regulatory uncertainty and resolve the dualism of the licensing regime[20], meaning it is now clear that all a non-integrated mining company needs is a sole IUI to carry out processing and/or refining under the purview of the MOI[21].

(V) Assignment of licenses

Prior to the introduction of the 2020 Mining Law, the assignment of licenses was also previously prohibited save for transfers to a related company (being a company in which the license holder held at least 51% of the shares) as part of an internal reorganisation. Mining license holders are now allowed to assign their licenses to any party with the MEMR’s approval but subject to satisfaction of certain conditions, at the minimum, being the completion of exploration activities (as evidenced by data on relevant resources) and certain administrative, technical, and financial requirements. Similarly, a transfer of shares in a mining license holder (or where there is a change of control) requires the prior approval of the MEMR, which would be granted upon satisfaction of the aforementioned conditions.

(VI) Divesture to Indonesian parties

Under the 2009 Mining Law, all foreign shareholders in IUP holders (meaning those mining companies specifically involved in mining, and not processing and/or refining activities[22]) were required to gradually divest its shares to Indonesian parties from the fifth year of commercial production, such that by the tenth year at least 51% of the company’s total issued shares are owned by Indonesian parties. Prior to the 2009 Mining Law coming into effect, this concept of divestiture in foreign-owned mining companies existed in the form of sell-down provisions drafted into their mining contracts. The 2009 Mining Law served to institute these sell-down provisions into law by enforcing the aforementioned obligation for foreign ownership divestment.

The 2020 Mining Law preserves but now varies divestment requirements depending on whether a foreign-invested mining company has integrated processing and/or refining facilities and the type of mining method undertaken. Noticeably, a foreign-invested mining company participating in open pit mining method without integrated mineral processing and/or refining facilities must comprise 51% shareholding of Indonesian parties by the fifteenth year after production commences. However, the same mining company using the same mining method but with integrated facilities would have an extra 5 years to adhere to this divestiture requirement, in other words by the twentieth year after production commences. In comparison, where the underground mining method is adopted without integrated facilities, the foreign-invested mining company must comprise 51% shareholding by the twentieth year or by the twenty-fifth year if there are facilities integrated[23].

In order of preference, divestments are to be made to the central government, the provincial or municipal government, state-owned or regional owned enterprise and last, domestic private business entity[24]. After being offered to the foregoing entities, unsold shares will be listed on the Indonesian stock exchange. A divestment may be conducted through the transfer or sale of the foreign shareholder’s existing shares or through the issuance of new shares to the selected entity. The divestment share price is calculated based on fair market value using the discounted cash flow method and/or market data benchmarking method and the MEMR may appoint an independent valuer to evaluate this price. Other divestment procedures including the timeline, the approval processes and the payment mechanism are enshrined in law by the MEMR[25]. In the scenario of non-adherence to the divestment requirements, this could invoke administrative sanctions which include written warnings, suspension of production and/or revocation of the IUP.

State-directed ownership and investment in the mining and battery sector

Of relevance, the Indonesian government has adopted a two-pronged approach to extend its influence in the nickel industry. Other than revamping legislation, the government holds direct and indirect interests in several state-owned companies in the mining and battery sector. Mining Industry Indonesia is fully owned by the Indonesian government and functions as a strategic holding company of the government’s interests in the mining sector, with shareholdings in Antam, Bukit Asam, Inalum, PT Freeport Indonesia, Indonesia Asahan Aluminium (Persero), PT Vale Indonesia and Timah. These companies are involved in almost all activities across the mining supply chain, starting from exploration, development, mining, and processing to the marketing of nickel ore.

In 2021, the Indonesian government also established Indonesia Battery Corporation (IBC) to accelerate the growth of the EV ecosystem. IBC is equally owned by four state-owned enterprises, namely Mining Industry Indonesia, its nickel-producing subsidiary Antam, oil and gas company Pertamina, and electricity utility PLN. As leaders in important sections of Indonesia’s EV value chain, they facilitate the development of Indonesia’s EV market as well as offer partnership and certainty to foreign investors. Each company has their respective responsibilities: Mining Industry Indonesia lends its strategic oversight to every aspect of the value chain which the other three subsidiaries are respectively in charge of, Antam is responsible for mining and processing raw minerals for batteries (in the form of nickel, cobalt, manganese and aluminium) while Pertamina and PLN are involved in the manufacture of battery cells and battery packs, as well as the construction of public EV charging stations.

Development of the downstream and EV battery manufacturing industry

In line with the creation of IBC and led by the government’s vision of building an end-to-end EV supply chain onshore, it comes as no surprise that the Indonesian government wants to offer potential investors access to Indonesia’s reserves of critical battery metals and its more than 270 million consumers to kickstart EV industry development and enter the global EV supply. The government, through IBC, has joined forces with a consortium led by LG and Hyundai to build the country’s first EV battery plant entailing a substantial investment of US$1.1 billion in its construction as part of a US$9.8 billion grand package to build battery production onshore[26]. The battery plant is currently being constructed in Karawang and is set to come online next year.

The encouragement of concerted integrated infrastructure development by the Indonesian government demonstrates its intent to develop the downstream supply chain on a broader scale. More domestic smelting facilities are to be built to encourage onshore processing of Class 2 nickel. In Sulawesi and Maluka islands to date, it is estimated that there are 43 operational nickel smelters with a further 28 power plants under construction and 24 in the planning stages in those regions[27]. The automotive industry’s access to battery-grade Class 1 nickel is also expanding with six HPAL plant projects under construction with another six in the planning stages[28].

Despite there being a significant potential for growth, there are nonetheless several obstacles laying on Indonesia’s path to success. For one, there is a lack of standardisation in the EV sector in part due to the type of batteries deployed. Each battery type requires a different charger and treatment based on its current and voltage. Moreover, the extraction process of the raw materials required to build battery components is associated with increased costs and environmental concerns (see our discussion on ESG issues and LFP batteries below). HPAL projects are also costly endeavours, with the level of investment about US$65,000 per tonne of nickel or about five times more than the conventional RKEF method[29]. In February this year, the Indonesian government announced their goal for Indonesia to become one of the top three producers of EV batteries by 2027. For Indonesia to compete in the increasingly competitive EV market, this entails significant investment and will require building up strong EV support infrastructure, leveraging its raw material supply to stabilize supply chains and securing adequate funding, a no small part of which is likely to come from foreign investment.

Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Issues

From an ESG perspective, the carbon intensity of Indonesia’s nickel sector attracts certain concerns. This poses an awkward challenge to EV manufacturers, bearing in mind the purpose of transitioning to EVs is to eliminate carbon emissions from transport. A McKinsey study found that the specific processing route of the type of nickel ore is an important driver of carbon dioxide emissions. As Indonesia’s nickel ores are lateritic (and not sulphide), the fossil fuel-based reducing agents used to smelt the lateritic ores emit higher carbon emissions (since fossil fuel elements are used) compared to the chemical-based reducing agents used to process sulphide ores[30]. The electricity source also drives the carbon intensity of a nickel processing operation. In the case of Indonesia, its laterite smelters are also energy-intensive production routes powered by the widespread use of captive coal. Indonesia’s industrial parks, which are centres for nickel and aluminium processing, currently account for 15% of the country’s coal power output[31], noting that the production of Class 1 nickel from Indonesia’s laterite ore resources releases two to six times the amount of carbon dioxide emissions compared to Class 2 nickel.

Apart from reduction of carbon emissions, there are other considerations presented by ESG requirements. For instance, waste management in an ESG-compliant way (particularly, the disposal of by-products in a contained area with limited ecosystem damage) is key for mining companies seeking to prove their green credentials. Since 2021, Indonesia has barred deep-sea tailings disposal (tailings being a by-product of extracting nickel metal from the ore) meaning land disposal of tailings would be the only alternative option. While there are certainly sustainable methods of treating and storing tailings, government oversight and regulation remains much needed as space and cost considerations lead to the risk of illegal dumping of mining waste.

Indonesia’s president Joko Widodo has recently pledged (in March this year) to promote responsible mining by only granting new smelter permits powered by renewable energy sources and for imposing deadlines on existing coal-powered facilities to switch to renewables[32]. However, there has been to date no new legislation or regulation introduced to support his pledge. The onus (and pressure) then falls on mining companies to take the initiative to universally explore new carbon reductionist techniques, such as the use of alternative fuels, asset electrification and efficient waste management. For instance, as a move towards low-carbon operations, certain mining companies in Indonesia are exploring the use of liquefied natural gas (LNG) as an energy source[33], while others are seeking to rely on renewable power to power their nickel processing operations[34]. Ultimately, the challenge to be overcome lies in the higher cost implications for relying on LNG and/or renewable power compared to domestic coal for power production. At least for the near future, coal will be a materially more economical option as a baseload power supply, especially given the relatively high energy consumption for nickel smelter and refinery facilities.

For many companies, ESG considerations go beyond purely compliance with domestic regulation – particularly, this is due to the growing prevalence of ESG reporting and sustainability disclosure requirements for publicly listed companies, the imposition of environmental and social standards by international lenders, as well as potential ESG requirements in regional or national battery subsidy programs. In 2017, the European Commission launched its €20 billion Battery Alliance subsidy program to boost sustainable battery production and usage[35]. As part of this program, the European Commission came up with mandatory requirements for all batteries placed on the EU market (such as use of responsibly sourced materials with restricted use of hazardous substances, tracking the carbon footprint and a minimum content of recycled materials) to ensure that its green subsidies promote the production of batteries in an environmentally friendly way. On the other hand, such requirements are by no means universally found in other EV or battery subsidy programs (for instance, the IRA (as further discussed below) does not currently promote such a linkage with its EV tax subsidy). That said, given the focus around sustainable mining practices for green metals, it is certainly conceivable, as part of the global move towards green economies, that future battery or EV subsidy programs will be increasingly linked to the sustainability profile of the raw material production for the battery or EV.

US-Indonesia Free Trade Agreement (FTA) and the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) issues

The passing of the IRA in 2022 (with its associated tax incentives) was seen as a potentially transformative piece of legislation for the EV industry and consumers in the United States (the US). Amongst other things, the IRA provides a US$7,500 consumer tax credit to domestic consumers if their newly purchased EV car meets the following sourcing requirements[36]:

- a total of 40% of the minerals used for EV battery production are extracted or processed in the US or (of relevance) with one of its free trade partners; and

- at least 50% of the battery components are manufactured or assembled in the US. Vehicles that meet one of the two requirements only qualify for a US$3,750 credit.

Currently, Indonesia does not have an FTA with the US. When the IRA first came into force, Indonesian businesses responded to the policy with concern since the lack of an FTA means EV batteries using critical minerals that they produced will be ineligible for the tax credits which in turn makes their products less competitive[37]. The Indonesian government has requested to kick-off discussions with the US on a limited FTA for Indonesia’s critical minerals (including nickel) so that its exports can be covered under the IRA. In essence, Indonesia believes the benefits of a limited US-Indonesia FTA when coupled with the IRA’s EV subsidy are twofold: the country will become more attractive to US car companies such as Tesla and Ford in its bid to become the (or at least one of the) supplier of choice for critical minerals used in their global supply chains to build EV batteries while opening up new markets to Indonesian companies situated on the burgeoning EV supply chain.

Apart from the absence of an Indonesia-US FTA, there is another potential snag: from 2024 onwards, an eligible EV may not contain any battery components that are manufactured by a “foreign entity of concern” and beginning in 2025 an eligible clean vehicle may not contain any critical minerals that were extracted, processed, or recycled by a “foreign entity of concern”. Guidance on identifying a “foreign entity of concern” in accordance with the IRA has not yet been issued by the US Department of Treasury. However, the US Department of Commerce’s interpretation of a “foreign entity of concern” under the CHIPS and Science Act (CHIPS Act) includes, inter alia, (i) any entity organized under the laws of China or having its principal place of business in China, and (ii) any entity organized outside of China with 25% or more of whose voting interests are owned by the Chinese government (as in the case of foreign subsidiaries of Chinese state-owned entities)[38]. If the same interpretation is applied to the IRA, this may pose a concern for a not insignificant proportion of critical minerals and battery components produced from Indonesia’s EV supply chain, noting that China is currently the most dominant actor across the entire lithium-ion battery value chain[39] as well as the large Chinese presence in Indonesia’s nickel mining industry as discussed above.

Guidance on the interpretation of the term “foreign entity of concern”, the application of such an interpretation in specific instances, and the responses of Chinese companies (in terms of project ownership and control structures) will be watched by the mining industry with keen interest.

The way forward

The global nickel market is projected to grow from around US$36 billion in 2021 to nearly US$60 billion in 2028[40]. Many see nickel as a key metal to power the green energy transition and with the potential to play this vital role on a global scale. Its properties facilitate the deployment of an entire spectrum of clean energy technologies: batteries for EVs and energy storage, hydrogen, wind and concentrating solar power, as a solution to the climate crisis.

Developing and maturing the nickel industry in Indonesia will face undoubted challenges, including those arising from the domestic regulatory and investment landscape, as well as the international environment and changes in the broader technical and technological landscape[41]. These challenges are unlikely to deter from the fact that there is a coordinated push to cement Indonesia’s position as the world’s largest producer of nickel for many years to come, and potentially also as a future manufacturing centre for batteries and EVs.

The country already bears fruit to some of the largest projects in the nickel sphere. If its ambitious plans in the nickel mining and battery sector are realised, then this will no doubt consolidate Indonesia’s status as a global producer of critical minerals and a key contributor to the green energy transition.

U.S. Department of Energy, “What are Critical Materials and Critical Minerals?”

Kitco News, “Global nickel production up 21% in 2022 as Indonesian output jumps 54%”: and Investing News Network, “Nickel Mines in Australia (Updated 2023)”

ASEAN Briefing, “Unleashing Nickel’s Potential: Indonesia’s Journey to Global Prominence”

The Lowy Institute, “Indonesia’s uncertain climb up the nickel value chain” and Reuters, “Indonesia’s FDI jumps in 2022, led by mineral processing”

The Rotary Kiln-Electric Furnace (RKEF) used to be the main method to produce Class 1 nickel and Class 2 nickel: a rotary drying kiln is first used to remove part of the water in the raw nickel ore. The RKEF lateritic nickel rotary kiln is then used to remove the remaining free and crystal water in the ore before preheating the ore to selectively reduce part of the nickel and iron into slag. This is followed by electric furnace smelting reduction whereby molten ferronickel is separated from the slag and refined for impurities before being poured into moulds for use (in the form of Class 2 nickel). Additional steps are required to obtain Class 1 nickel: elemental sulphur is added to the ferronickel in a converter where it is blown with air to oxidize and separate iron so as to produce a high-grade nickel matte which will undergo refinement into Class 1 nickel.

Regulation of the Minister of Trade of the Republic of Indonesia Number 1/2017 concerning export provisions for processed and purified mining products of 9 January 2017.

The 2009 Mining Law classified three types of mining licenses: IUP, IPR and IUPK, all of which are granted by a government tender process. For background, an IUP is a general license to conduct mining business activities in a mining business permit area whereas an IPR is a community mining license issued to small and medium-scale local mining operators and an IUPK is a special license to conduct such activities in a specific protected area e.g. nature reserves. The 2020 Mining Law expanded on this by introducing several new types: Rock Mining Permission Letter, Assignment Permit, Transportation and Sale License, Mining Service Business License and IUP for Sales. Although these licenses are now issued by the central government through the MEMR, the 2020 Mining Law allows the delegation of such matters to the regional government in accordance with the prevailing law.

Mining licences can only be granted to Indonesian legal entities, a foreign entity cannot directly own the licensing rights and so must establish an Indonesian legal entity in the form of a foreign investment company which will be subject to partial divestment of its shares at certain milestones to be discussed below.

Under the 2009 Mining Law, an Exploration IUP holder was guaranteed to receive a Production Operation IUP provided it complied with the terms of its Exploration IUP during the exploration stage and applied to upgrade to a Production Operation IUP at least 12 months (but not more than 5 years) before the end of the current period of its Exploration IUP. A party that wished to circumvent the exploratory stage and jump straight into the processing and/or refining activities would have to obtain a Special Production Operation IUP instead, see our discussion in section B(IV) below.

From a commercial standpoint, a non-integrated mining company provides structuring flexibilities between the upstream mining asset and the downstream refining and processing asset given that separate entities with different stakeholders can hold each asset, with a different set of financing structures and also indirectly avoid “divesting” the downstream asset when the mandatory divestment obligation kicks in for the upstream mining asset where foreign shareholders are involved.

Existing holders of Special Production Operation IUPs were given a grace period of 1 year from the date of the 2020 Mining Law coming into effect to convert their IUPs into IUIs.

With reference to footnote 18 and under the 2009 Mining Law, a Special Production IUP and IUI was required for a mining company to carry out downstream processing/refining while an Exploration IUP (and then a Production Operation IUP) was required for a mining company to carry out both upstream mining and downstream processing/refining. The advent of the 2020 Mining Law abolished Special Production IUPs so that a mining company engaged in downstream processing/refining only requires an IUI whereas a mining company engaged in both upstream and downstream only requires a singular ‘Mining Business License’ IUP (see our discussion in section B(II) above).

Non-integrated mining companies are not subject to the divestiture requirement, see our discussion in footnote 19 above on the practicalities of forming a non-integrated mining company.

Article 147 of Government Regulation No. 96 of 2021 read with Law No. 3 of 2020.

Where there is interest from more than one party, the MEMR shall coordinate the determination of the number of divested shares to be purchased by the interested parties.

On 8 April 2020, the MEMR issued MEMR Decree No. 84 K/32/MEM/2020 of 2020 which stipulates the detailed requirements for the implementation of a divestment.

Katada (8 April 2021), “Archandra Tahar Ungkap Tantangan Produksi Baterai Kendaraan Listrik”.

McKinsey & Company, “Pressure to decarbonize: Drivers of mine-side emissions”

Mining Technology, “Indonesia pledges nickel mining clean up amid EV-led boom”

A recent example being the Bahodopi Project in Central Sulawesi (a joint venture between Vale S.A. and Taiyuan Iron and Steel Group) which is transitioning away from coal by using LNG exclusively as an energy source. Vale S.A.’s other Indonesian assets will also move to natural gas in a phased manner by 2030. See here.

Nickel Industries is building a solar farm project to power its nickel processing operations within Morowali Industrial Park (MIP). MIP itself is upgrading its complex’s operations by also constructing solar panels and converting to electric trucks. See https://www.miningweekly.com/article/nickel-industries-signs-term-sheet-for-battery-solar-project-2022-08-17 and https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-07-24/indonesian-nickel-mine-morowali-takes-steps-to-address-environmental-concerns.

The program dispenses subsidies to support the research programs of European SMEs and start-ups looking into the development of novel production processes and other innovations in the battery value chain to advance an innovative and sustainable European battery industry.

The applicable percentages for (i) and (ii) are mandated to increase in each subsequent year. For (i): For 2023, the applicable percentage is 40% and this figure will increase by 10% each year until beginning in 2027 onwards, the applicable percentage will be fixed at 80%. For (ii): For 2023, the applicable percentage is 50%, for 2024 and 2025, the applicable percentage is 60% and this figure will increase by 10% each year thereafter until beginning in 2029 onwards whereby the applicable percentage will be fixed at 100%.

The Jakarta Post, “China may be hindrance in RI getting FTA with US on critical minerals”

15 CFR 231.106(c) read with 15 CFR 231.112 when applied to a “foreign entity of concern” which is defined under 10 USC 2533c(d)(2) to mean China, North Korea, Russia and Iran.

Center on Global Energy Policy, “The IRA and the US Battery Supply Chain: Background and Key Drivers”

Fortune Business Insights, “Nickel Market Size, Share & COVID-19 Impact Analysis, By Application (Stainless Steel, Special Steels, Batteries, Electroplating, Alloys, and Others), and Regional Forecast, 2021-2028”

Of recent relevance, lithium ferrous phosphate (LFP) batteries have been gaining traction in China and America. China’s LFP output has surpassed nickel-based batteries since May 2021 with Tesla switching from lithium-ion batteries (which contain nickel) to LFP batteries for cars sold in China and Ford’s US$3.5 billion LFP factory in Michigan to begin production in 2026. Despite offering a lower voltage and lower energy density, LFP batteries achieve the same functionality as lithium-ion batteries and last a longer life cycle at a lower cost - Iron and phosphate are used in the cathode of an LFP battery, both are 20% cheaper and easier to source than nickel. If this trend continues, LFP batteries may be preferred over nickel-based batteries for EVs globally as carmakers aim for cost efficiencies.